RECEIVING THE TEACHINGS

The best approach to receiving oral and written spiritual teachings is to "hear, conclude, and experience," that is, intellectually understand what is said, conclude what is meant, and apply it in practice. If learning is approached this way, the process of learning is continuous and unceasing, but if it stops at the level of the intellect, it can become a barrier to practice.

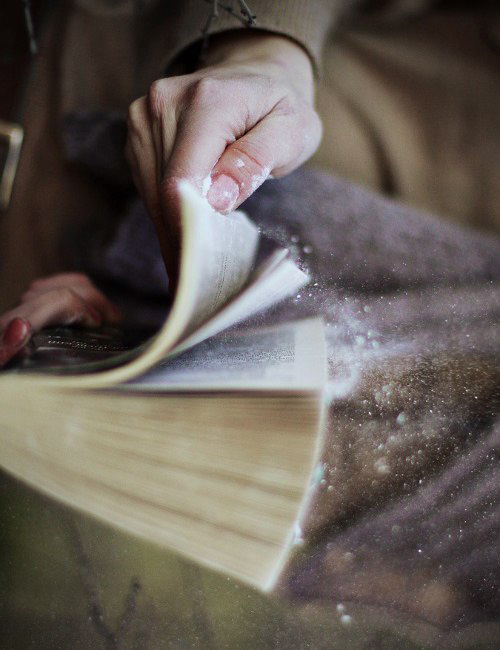

As to hearing or receiving the teachings, the good student is like a gluecovered wall: weeds thrown against it stick to it. A bad student is like a dry wall: what is tossed against it slides to the floor. When the teachings are received, they should not be lost or wasted. The student should retain the teachings in his or her mind, and work with them. Teachings not penetrated with understanding are like weeds thrown against the dry wall; they fall to the floor and are forgotten.

Coming to the conclusion of the meaning of teachings is like turning on a light in a dark room: what was hidden becomes clear. It is the experience of "a-ha!" when the pieces click into place and are understood. It's different from simple conceptual understanding in that it is something we know rather than something we have merely heard. For example, being told about yellow and red cushions in a room is like gaining an intellectual understanding of them, but if we go into the room when it is dark, we cannot tell which cushion is which. Concluding the meaning is like turning the light on: then we directly know the red and the yellow. The teaching is no longer something we can only repeat, it is part of us.

By "applying in practice," we mean turning what has been conceptually understood what has been received, pondered, and made meaningful into direct experience. This process is analogous to tasting salt. Salt can be talked about, its chemical nature understood, and so on, but the direct experience is had when it is tasted. That experience cannot be grasped intellectually and cannot be conveyed in words. If we try to explain it to someone who has never tasted salt, they will not be able to understand what it is that we have experienced. But when we talk of it to someone who already has had the experience, then we both know what is being referred to. It is the same with the teachings. This is how to study them: hear or read them, think about them, conclude the meaning, and find the meaning in direct experience.

In Tibet, new leather skins are put in the sun and rubbed with butter to make them softer. The practitioner is like the new skin, tough and hard with narrow views and conceptual rigidity. The teaching (dharma*) is like the butter, rubbed in through practice, and the sun is like direct experience; when both are applied the practitioner becomes soft and pliable.

But butter is also stored in leather bags. When butter is left in a bag for some years, the leather of the bag becomes hard as wood and no amount of new butter can soften it. Someone who spends many years studying the teachings, intellectualizing a great deal with little experience of practice, is like that hardened leather.

The teachings can soften the hard skin of ignorance and conditioning, but when they are stored in the intellect and not rubbed into the practitioner with practice and warmed with direct experience, that person may become rigid and hard in his intellectual understanding. Then new teachings will not soften him, will not penetrate and change him. We must be careful not to store up the teachings as only conceptual understanding lest that conceptual understanding becomes a block to wisdom.

The teachings are not ideas to be collected, but a path to be followed.

Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche (1998). The Tibetan Yogas of Dream and Sleep.